Spoiler Alert: It’s impossible to discuss this film meaningfully without giving out the storyline, same with the two prequels.

***

We are gleaners of memories. An interesting parallel applies to the two characters Celine and Jesse as well as ourselves as audience. But if you haven’t seen Before Sunrise and Before Sunset, it would enhance your viewing pleasure to watch them first.

Flashback: Before Sunrise (1995)

Two young people, Parisian Celine (Julie Delpy) and American Jesse (Ethan Hawkes) meet on a train passing through Europe. They strike up a conversation and become so in-tuned with each other that when the train arrives Jesse’s stop in Vienna, he convinces Celine to get off with him even though her destination is Paris. There for just one night until sunrise, they walk around the city and talk about life, death, love, religion, relationships, and being transients… for they know this may well be their only encounter with each other in both of their lives. The next morning Jesse has to fly back to the U.S. As they part, they promise to meet again in six month at the same hour, on the same train platform. Throughout the film, we feel fate, or whatever you call it, has a strong presence in their short few hours together. We feel their sincerity in capturing those precious moments, as we hear Celine’s words ring true:

Two young people, Parisian Celine (Julie Delpy) and American Jesse (Ethan Hawkes) meet on a train passing through Europe. They strike up a conversation and become so in-tuned with each other that when the train arrives Jesse’s stop in Vienna, he convinces Celine to get off with him even though her destination is Paris. There for just one night until sunrise, they walk around the city and talk about life, death, love, religion, relationships, and being transients… for they know this may well be their only encounter with each other in both of their lives. The next morning Jesse has to fly back to the U.S. As they part, they promise to meet again in six month at the same hour, on the same train platform. Throughout the film, we feel fate, or whatever you call it, has a strong presence in their short few hours together. We feel their sincerity in capturing those precious moments, as we hear Celine’s words ring true:

“If there’s any kind of magic in this world… it must be in the attempt of understanding someone sharing something.”

Flashback: Before Sunset (2004)

Nine years after that chance meeting, Jesse is in Paris on the last leg of a book tour. He has written a book based on that memorable encounter nine years ago. At the Shakespeare and Company bookstore, Celine shows up. They now meet for a second time, again for a short few hours before Jesse has to leave on a plane to fly back to the U.S. Their conversation reveals that, alas, their well intended reunion six months after their first chance meeting has turned into a star-crossed, missed opportunity. After that, fate has led them down separate paths. Jesse is now married and has a son. Celine, still on her own, yearns for that first romance to develop but now seems even more elusive.

Nine years after that chance meeting, Jesse is in Paris on the last leg of a book tour. He has written a book based on that memorable encounter nine years ago. At the Shakespeare and Company bookstore, Celine shows up. They now meet for a second time, again for a short few hours before Jesse has to leave on a plane to fly back to the U.S. Their conversation reveals that, alas, their well intended reunion six months after their first chance meeting has turned into a star-crossed, missed opportunity. After that, fate has led them down separate paths. Jesse is now married and has a son. Celine, still on her own, yearns for that first romance to develop but now seems even more elusive.

To the present: Before Midnight (2013)

So we have been following Jesse and Celine like a longitudinal study, albeit meeting them just twice within this eighteen year period. In the first two films, director Richard Linklater has us follow Jesse and Celine in real time through long takes, walking along with them in Vienna and Paris, listening in on their conversations and see them pour their hearts out, just to be heard, to be known. Those were romantic moments. This time is summer in Greece; this time is reality check.

We see Jesse and Celine now married. What happens in between those nine years is that Jesse has divorced his wife in Chicago, come over to Paris, married Celine and together they have two lovely twin daughters. But things aren’t so idyllic, for Jesse is troubled by not being around for his now young teenaged son Hank from his previous marriage and whom he can only see in the summer. The film begins with Jesse seeing his son off at the airport.

For the next 15 minutes and in one stationary take through the front windshield of the car, we see a happy couple Jesse and Celine driving from the airport to a Greek country house, with their twin daughters sleeping in the backseat. We hear them talk, yes, they love to talk to each other, just as we’ve seen in the past.

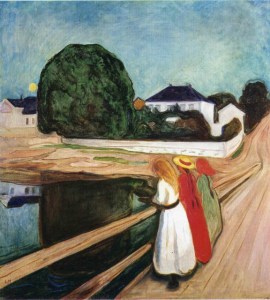

In the setting of an idyllic seaside residence, Jesse and Celine join a small gathering of writers. we see them prepare and eat healthy Greek salads and discuss equally idyllic topics such as writing, love, knowing each other, virtual reality (yes, for the contemporary effect), and being transients in life. Again, that first train encounter comes to mind. In conclusion they drink to ‘passing through’.

The next act is reminiscence of previous Before films… Jesse and Celine walk to a hotel paid for by their writer friends, who have also taken up the duty of babysitting their twins so the two of them can fully enjoy each other for the night. For twenty minutes the camera follows them in real time strolling through some scenic rural town toward their country hotel, exchanging thoughts like before. But no, not totally like before, for now they are eighteen years older, 41, and each with emotional undercurrents running deep.

Five minutes in the hotel room, discordant riptides begin to surface. Talk turns into quarrel. Why, this is just too real. In the past, we see them only in romantic mode. Now as they expose their underlying thoughts and suspicions, tempers flare, words turn callous. We would silently say ‘ouch!’ occasionally.

The beginning scene of the first film, Before Sunrise, has become a stark foreshadowing… sitting near Jesse and Celine on that train, two middle-aged couple argue fiercely in German. Seeing their temper flare but not understanding what they were arguing about, Jesse and Celine ponder on the question of how two people can grow old together in harmony.

Now here in what is supposed to be an ideal get-away, for twenty minutes we are the invisible witnesses of a marital conflict, and we would want to stay in there to see what happens next, not because of the schadenfreude effect, but because this is just too real.

Romance is holiday, marriage is work.

Hawke and Delpy own these scenes depicting realistically what marriage could entail. Other films readily come to mind… Ingmar Bergman’s Scenes From A Marriage (1973) and Woody Allen’s Husbands and Wives (1992). Before Midnight is a contemporary version, with a highly watchable backdrop and natural performance. Unlike Bergman and Allen, Linklater is commendable in crafting a more positive ending. It’s refreshing to see a glimmer of hope at the end of nasty quarrels.

In the final act, Jesse attempts to woo his wife back. How he does it is most endearing. Every moment in the present is an opportunity to create a fond memory to look back to in the future. This complicated package called love is a piece of work. Director Linklater and his two stars, who co-wrote the screenplay with him, might well have passed to us the secret of marital success… Before too late, glean fond memories from the past to sustain the relationship at present; before too late, create more loving memories to carry it into the future.

One line from Celine in Before Sunset is most apt here: “Memory is a wonderful thing if we don’t have to deal with the past.” Jesse might have known this too well, not to leave the present a mess for future to deal with, but leave it as a pleasant memory to cherish in the days ahead.

With a trilogy of films beginning with the word ‘Before’ in the title, we should know that time is of the essence. Time to make the present a memorable past for the future, before too late.

That line still lingers as the film ends… ‘To passing through.’

~ ~ ~ 1/2 Ripples for all three films

***