Surely he has borne our griefs

and carried our sorrows;

yet we esteemed him stricken,

smitten by God, and afflicted.

— Isaiah 53:4 ESV

Several days before He is crucified, Jesus enters Jerusalem riding on a donkey. I love this scene. If there’s any cognitive dissonance in the crowd, here’s the stark message for their bewilderment. The King for whom they are cheering is not to be a glamorous celebrity. Rather, like the donkey, He comes as a humble servant, one who carries their load, and ultimately, even lays down his life for them. His kingdom belongs to another world.

As with my Easter viewing from previous years, I watch a film by the French auteur Robert Bresson. Bresson’s work has a transcending and spiritual quality that is deeply moving. In Au Hasard Balthazar, he creates an unusual metaphor using a donkey as his protagonist. We follow Balthazar as a young colt, loved by his first owner Marie. We see him grow up, weaving his life among different owners. We also see Marie grow up. Despite her love for Balthazar, she cannot stop the encroachment of evil, or maybe she is simply powerless. She does not defend Balthazar when a gang of young men abuse the donkey, tormenting him, whipping, mocking.

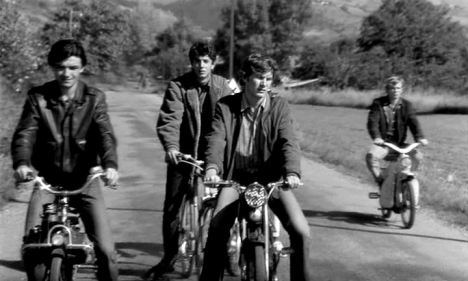

The gang leader is Gérard, whose sadistic, mean streak speaks for human depravity. He would pour gasoline on the road to cause unsuspecting drivers to skid and crash. He and his gang would watch nonchalantly from a distance, gratified that their prank has worked. He steals and deceives. What is a donkey to him if he does not even have the slightest respect for other humans. Once, to prod Balthazar to move forward, Gérard ties a newspaper to his tail and light it on fire.

Throughout, Balthazar lives his life quietly in a parallel course to the growing depravity of the humans he serves. He suffers their cruelty in silence, occasionally he would bray in pain, but he continues to bear his load, pull a cart, or do whatever he is prodded to do, even a circus act. Due to neglect and maltreatment, he often becomes ill.

As she grows up, Marie discards childhood innocence and seeks to gratify her sensual pleasures. Against the protest of her parents, she falls for Gérard. She could have another choice, one who offers her genuine love, Jacques, the son of the owner of the farm where Marie and her parents reside. Jacque would come by every summer from the city with his father and sister to stay on the farm. When they were still children, they had spent endearing moments together with Balthazar. Jacques has declared lifelong commitment to Marie. But Gérard is a more instant and attractive outlet for Marie. Ultimately, she is dealt the harshest blow and most degrading abuse from Gérard and his gang as they rape her. Bresson spares us the ugly scene, but in the chilling aftermath, we see the young men walk away, nonchalant, throwing her garments on the ground behind them. After that tragic incident, Marie runs away. Her father is grief stricken, and soon falls ill and dies.

Gérard is unrepentant. After all, it’s self-serving lust he seeks; his callousness is most disturbing. In the last scene, we see he uses Balthazar to do one more job for his gang. They are to smuggle goods across the mountainous border. At night, he loads up his goods on the donkey and leads him to the border. From a distance, he hears gun shots from armed customs police. Gerard and his gang flee, abandoning Balthazar on the mountain. But it’s too late for Balthazar, he has been shot.

The final scene is most moving. In the open field, Balthazar walks slowly, haggard, blood streaming from his leg. He finally lies down, still carrying the goods Gérard has put on him, the load of sin. He breathes his last and quietly dies, alone.

Like Bresson’s Diary of a Country Priest, Au Hasard Balthazar is an apt meditation for Good Friday. But not just for this one day, their timeless message is like the Easter Season itself, a moveable feast.

~ ~ ~ ~ Ripples

***

Related Posts and Links:

Diary of a Country Priest: A Book For Easter