Recently I’ve just finished reading Paul Schrader’s Transcendental Style in Film: Ozu, Bresson, Dreyer (1972). Yes, that’s before Schrader rose to prominence as a screenwriter and filmmaker. Is such a book a bit dated? Considering the techno-reigning world we’re living in now, where speed is measured by nanoseconds, and where 3D and CGI have become the necessary features for movies to generate sales, I think we need to read this all the more.

The three directors in the book had produced some of the best movies of all time. Since I have not seen all the films Schrader discusses, I might not have grasped as fully his arguments and illustrations as they deserve. And I admit I do not embrace unquestionably all those that I do get. Nevertheless, there are many, many parts that I want to record down. I’d consider them crucial elements to mull over during the creative process in just about anything. I’ve listed some of these fine quotes in the following.

They all point to the axiom of ‘less is more’, the value of stillness and simplicity, the speechless sketch that speaks volumes, the importance of being over doing, the quality of sparseness over abundance, the bare essence of life.

Notes to myself: when watching, writing, reading, doing, or just plain walking down the mundane path of everyday, keep these points in mind.

- Ozu’s camera is always at the level of a person seated in traditional fashion on the tatami, about three feet above the ground. “This traditional view is the view in repose, commanding a very limited field of vision. It is the attitude for watching, for listening, it is the position from which one sees the Noh… It is the aesthetic attitude; it is the passive attitude.”[1]

- Ozu chose his actors not for their “star” quality or acting skill, but for their “essential” quality. “In casting it is not a matter of skilfulness or lack of skill an actor has. It is what he is…”

- “Pictures with obvious plots bore me now,” Ozu told Richie. “Naturally, a film must have some kind of structure or else it is not a film, but I feel that a picture isn’t good if it has too much drama or action… I want to portray a man’s character by eliminating all the dramatic devices. I want to make people feel what life is like without delineating all the dramatic up’s and downs.”

. - His films are characterized by “an abstentious rigor, a concern for brevity and economy, an aspiring to the ultimate in limitation.”

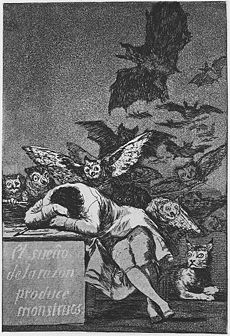

- Given a selection of inflections, the choice is monotone; a choice of sounds, the choice is silence; a selection of actions, the choice is stillness–there is no question of “reality”. It is obvious why a transcendental artist in cinema (the “realistic” medium) would choose such a representation of life: it prepares reality for the intrusion of the Transcendent…

- “The opening five shots of An Autumn Afternoon: The everyday celebrates the bare threshold of existence; it meticulously sets up the straw man of day-to-day reality.”

- In films of transcendental style, irony is the temporary solution to living in a schizoid world. The principal characters take an attitude of detached awareness, find humor in the bad as well as the good, passing judgment on nothing.

***

.

- Like Ozu, Bresson has an antipathy toward plot: “I try more and more in my films to suppress what people call plot. Plot is a novelist’s trick.”

- As far as I can I eliminate anything which may distract from the interior drama. For me, the cinema is an exploration within. Within the mind, the cinema can do anything.”

- On the surface there would seem little to link Ozu and Bresson… But their common desire to express the Transcendent on film made that link crucial… Transcendental style can express the endemic metaphors of each culture: it is like the mountain which is a mountain, doesn’t seem to be a mountain, then is a mountain again.

. - The abundant means sustain the viewer’s (or reader’s or listener’s) physical existence, that is, they maintain his interest; the sparse means, meanwhile, elevate his soul. The abundant means are sensual, emotional, humanistic, individualistic. They are characterized by realistic portraiture, three-dimensionality…

. - The “religious” film, either of the “spectacular” or “inspirational” variety, provides the most common example of the overuse of the abundant artistic means… the abundant means are indeed tempting to a filmmaker, especially if he is bent on proselytizing. (Now… why am I thinking of Avatar?)

- The transcendental style in films is unified with the transcendental style in any art, mosaics, painting, flower-arranging, tea ceremony, liturgy. At this point the function of religious art is complete; it may now fade back into experience. The wind blows where it will; it doesn’t matter once all is grace.

***

Transcendental Style In Film: Ozu, Bresson, Dreyer, published by University of California Press, 1972. 194 pages.

[1] Schrader quoting Donald Richie, “The Later Films of Yasujiro Ozu,” Film Quarterly, 13 (Fall 1959), p. 21.

The following three quotes are from the same source.

.

Some informative links:

Paul Schrader http://www.paulschrader.org/, http://www.imdb.com/name/nm0001707/

Donald Richie http://www.movingimagesource.us/dialogues/view/274

Yasujiru Ozu http://www.guardian.co.uk/film/2010/jan/09/yasujiro-ozu-ian-buruma, http://www.a2pcinema.com/ozu-san/home.htm

Robert Bresson http://www.mastersofcinema.org/bresson/, http://www.imdb.com/name/nm0000975/

Carl Theodor Dreyer http://archive.sensesofcinema.com/contents/directors/02/dreyer.html

David Bordwell http://www.davidbordwell.net/

***