The first ‘Snow Country’ in the title refers to the 1968 Japanese Nobel Laureate Yasunari Kawabata’s (川端 康成 1899-1972) seminal novel Snow Country (雪鄉); the second refers to Arti’s neck of the woods here north of the 49th parallel in mid December.

Written in the 1930’s through to the 1940’s, Snow Country was later translated into English and published in 1956. It is probably Kawabata’s most well-known work. Translator Edward G. Seidensticker had been credited for leading Kawabata’s work to the ultimate accolade, the Nobel Prize of Literature in 1968, a first for a Japanese writer.

The haiku-like simplicity so pervasive in the book is most apt for the Season. Firstly, its meditative descriptions and imagery offer a respite in the midst of our frantic pace. And secondly, it points to certain relevance during this Christmas time, which I find surprising.

Translator Seidensticker writes in the introduction that the haiku is a juxtaposition of incongruous terms, such as motion and stillness. Within such contradictions sparks “a sudden awareness of beauty.” Relax in the following poetic imageries:

They came out of the cedar grove, where the quiet seemed to fall in chilly drops.

or this:

[Her voice] seemed to come back like an echo of distilled love.

or this:

The field of white flowers on red stems was quietness itself.

Or savor the interplay of light and shadow, which evokes the poignancy of decayed beauty. This could well be the summing up of the human condition in Kawabata’s novel.

The sky was clouding over. Mountains still in the sunlight stood out against shadowed mountains. The play of light and shade changed from moment to moment, sketching a chilly landscape. Presently the ski grounds too were in shadow. Below the window Shimamura could see little needles of frost like ising-glass among the withered chrysanthemums, though water was still dripping from the snow on the roof.

The protagonist Shimamura, ‘who lived a life of idleness’ from inherited wealth, would leave his wife and children in Tokyo and go alone to the snow country every year, the mountain region of central Japan, to meet Komako, a young geisha at a hot spring village. The love affair between the two is starkly off-balanced. Despite her work in the pleasure quarters, entertaining parties of men, Komako is deeply devoted to Shimamura. Like her meager dwelling in the shabbiness of all, her room is spotlessly clean: “I want to be as clean and neat as the place will let me…”

Sadly, Komako realizes it is but a doomed unrequited love that she has invested in. Shimamura too is aware of his own coldness. Even though he is drawn back to Komako by making these trips to the snow country, he feels no obligation at all:

All of Komako came to him, but it seemed that nothing went out from him to her.

Of course, it could well be guilt and a sense of moral ground, albeit his loyalty to his wife and children rarely comes to mind.

Shimamura does not understand the purity Komako seeks in her love for him, and her desire not to be treated as a geisha. And that is why his nonchalant statement hits Komako so hard. In the climatic scene of the story, he utters, though not without affection: “You are a good woman.”

Instead of taking his words as an endearment, Komako is deeply hurt. Despite having to work as a geisha due to her circumstance, thus selling herself as an outcast, she longs to be removed from her predicament and be transported to a new life. Shimamura’s repeated words “You are a good woman” fall upon her like the gavel of final judgement laden with biting sarcasm.

Kawabata’s characters cry out for redemption, to be delivered from their precarious state. Komako is seeking saving grace in Shimamura, and desperately hoping for a way out of the “indefinable air of loneliness” shrouding her. But her search is in vain for the man is incapable of love:

He was conscious of an emptiness that made him see Komako’s life as beautiful but wasted, even though he himself was the object of her love; and yet the woman’s existence, her straining to live, came touching him like naked skin. He pitied her, and he pitied himself.

Shimamura knows deep down that he needs cleansing as much as or even more than Komako.

The snow country of Japan is also the land of the Chijimi. It is an old folk art of weaving where a certain kind of long grass is cut and treated, finally transformed into pure white thread. The whole process of spinning, weaving, washing and bleaching is done in the snow. As the saying goes, “There is Chijimi linen because there is snow.” After the linen is made into kimonos, people still send them back to the mountain regions to have the maidens who made them rebleach them each year. And this is where the universal appeal of snow as a metaphor for purity and cleansing so powerfully depicted by Kawabata, as Shimamura ponders:

The thought of the white linen, spread out on the deep snow, the cloth and the snow glowing scarlet in the rising sun, was enough to make him feel that the dirt of the summer had been washed away, even that he himself had been bleached clean.

When I came to this description towards the end of the book, a starkly similar image conjured up in my mind:

Though your sins are like scarlet, they shall be as white as snow; though they are red as crimson, they shall be like wool.” —- Isaiah 1:18

And like the doomed ending of their love affair, death comes as a certainty to all, insects or humans alike. Shimamura has observed how a moth “fell like a leaf from a tree… dragonflies bobbing about in countless swarms, like dandelion floss in the wind.” The poetic descriptions do not make death any more appealing. Kawabata uses insects as a metaphor for the frailty of life and the chilling finality awaiting:

Each day, as the autumn grew colder, insects died on the floor of his room. Stiff-winged insects fell on their backs and were unable to get to their feet again. A bee walked a little and collapsed, walked a little and collapsed. It was a quiet death that came with the change of seasons. Looking closely, however, Shimamura could see that the legs and feelers were trembling in the struggle to live.

It is pure serendipity that I picked up this book to read at this time of the year. The Christmas story too has also cast a vivid interplay between darkness and light. I was reminded of this reference:

The people walking in darkness have seen a great light; on those living in the land of the shadow of death a light has dawned.” — Isaiah 9:2

There is reason to rejoice, for the Able Deliverer had come… He too had lived a life of paradoxes and contradictions: born to die, life through death, strength through weakness. And beneath the surface of jollity of the Season and the superficial exchanges of good will, there lies deep and quiet, the source of joy and inner fulfillment, and Life’s ultimate triumph over death.

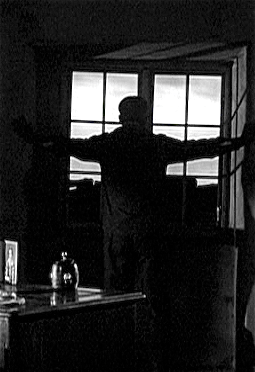

I heard a small voice echo as I treaded on the snowy path alone in my snow country.

It said: “For this reason I came.”

***

Snow Country by Yasunari Kawabata, translated by Edward G. Seidensticker. Published by Vintage International, 1996. 175 pages.

This concludes my final entry to meet Dolce Bellezza’s Japanese Literature Challenge 4 before the end of 2010.

My other JLC posts:

Never Let Me Go by Kazuo Ishiguro

Rouse Up O Young Men of the New Age! by Kenzaburo Oe