Part 2 of Sherry Turkle’s book Alone Together presents the networked self. Turkle has been called ‘the anthropologist of cyberspace.’ Her book reads like an ethnography of our human society today. While in Part 1 (my previous post) she has shown how we are receptive to robotics to solve our problems, Part 2 paints a picture of how we have embraced digital technology to seek the connections that we crave. The social media phenom is no longer the exclusive description of the young. Turkle cites that “the fastest-growing demographic on Facebook is adults from thirty-five to forty-four.”

I’ve found some more recent data (August, 2010) indicating that social networking use among Internet users age 50 and above has increased from 22% to 42% in one year. Now, more than ever, the popularity of social networking has permeated into all strata of our demographics.

This latter part of Turkle’s book addresses some of the consequences.

The Tethered Self

First off, we’re always on, no down time. Especially those with a smart phone, it keeps us connected no matter where we are. Turkle has provided us with numerous examples like Robin, 26, a copywriter in a demanding advertising agency:

If I’m not in touch, I feel almost dizzy. As though something is wrong, something terrible is wrong.

Check where you put your cell phone when you go out. In your pocket? Purse? Where you put it may well indicate how tethered and dependent you are.

Robin holds her BlackBerry; at meals, she sets it on the table near her, touching it frequently.

So you think you can place it out of reach. An art critic with a book deadline took drastic measures:

I went away to a cabin. And I left my cell phone in the car. In the trunk. My idea was that maybe I would check it once a day. I kept walking out of the house to open the trunk and check the phone. I felt like an addict…

As to the form of communication, emails have already become obsolete among those 25 and younger. They use emails only for more ‘formal’ purposes, like job hunting. Texting is more instant and casual.

Needless to say, the telephone has become archaic among the young:

‘So many people hate the telephone,’ says Elaine, seventeen… ‘It’s all texting and messaging.’

A sixteen year-old says:

When you text, you have more time to think about what you’re writing… On the telephone, too much might show.

Turkle notes that such a phenomenon may be more wide-spread than we think. She writes:

Teenagers flee the telephone. Perhaps more surprisingly, so do adults. They claim exhaustion and lack of time; always on call, with their time highly leveraged through multitasking, they avoid voice communication outside of a small circle because it demands their full attention when they don’t want to give it.

Not only that, the real security of non-face-to-face and voiceless communication is the safety it offers. Behind the screen, one can hide… “On the telephone, too much might show.”

Of course, we must not deny the benefits of technology, especially for parents with children. A cell phone is probably the best assurance parents can have. For those with college-age children, we too can constantly keep in contact through all sorts of features on our mobile devices. But beyond the effect of tethering, what have social media and our über connected society done to our values? Turkle notes:

These days, cultural norms are rapidly shifting. We used to equate growing up with the ability to function independently. These days always-on connection leads us to reconsider the virtues of a more collaborative self. All questions about autonomy look different if, on a daily basis, we are together even when we are alone. (p. 169)

Indeed, collaboration has become the virtue of our time… whether it is a school project, or a creative endeavor, or a business plan. But for one who prize independent thinking and solitary quietude, I can’t help but ponder the downside of perfunctory collaboration. It could be a good thing if it is collective wisdom at work. Nevertheless, what if it is mass sentiment, or, as the popular notion today, a view ‘gone viral’. Our ‘likes’ and ‘dislikes’ seem to be influenced more and more by what others are saying. Is there a place for independent thinking? Can we still preserve some privacy of mind, carve out a solitude just reserved for our own thoughts and feelings, insulated from the madding crowd? Or, is such a piece of solitude even desirable anymore?

.

.

Avatars and Identities

But it may not be all about business, or connecting with real life friends and associates that technology has made possible. Cyberspace has allowed us to adopt a different identity, building another life altogether. Avatars and online games have made it possible for one to take on multiple roles, all of them just as real. Using their mobile devices, people transport themselves to different realities simultaneously as they are living their real life in the here and now.

And it is this part of the book that is most disturbing to me.

In one of Turkle’s studies, she follows Pete, 46, bringing his children to the playground one Sunday. Turkle observes adults there divide their attention between children and their mobile devices, at which I’m no longer surprised. But here’s the twist to Pete’s case. With one hand, Pete pushes his six year-old on the swing, and with his other hand he uses his cell phone to step into his other identity, an Avatar called ‘Rolo’ in Second Life, a virtual place that is “not a game because there’s no winning, only living”.

Pete lives as ‘Rolo’ in Second Life. He is married to ‘Jade’, another Avatar, after an “elaborate Second Life ceremony more than a year before, surrounded by their virtual best friends.” Pete has an intimate relationship with Jade, whom he describes as “intelligent, passionate, and easy to talk to”, even though he knows very well that ‘Jade’ could be anyone, of any age and gender. Here’s what Pete says about his other married life:

Second Life gives me a better relationship than I have in real life. This is where I feel most myself. Jade accepts who I am. My relationship with Jade makes it possible for me to stay in my marriage, with my family.

Borders sure have blurred in our digital age. Is this considered a kind of extramarital affair? To Pete, this virtual marriage is an essential part of his life-mix, another of our postmodern notions. Life-mix is “the mash-up of what you have on- and off-line.”

So, it’s no longer “multi-tasking” any more, but “multi-lifing”. With all the avatars we can claim online, we can have multiple identities. I can’t help but ask: But which one is real? I also wonder how many are projecting their real-life identity and true self on Facebook, blogs or Twitter? But the ultimate questions probably would be: What is ‘real life’ anyway, or the ‘true self’? Does ‘authenticity’ still matter? Is it even definable?

Part 1 of Alone Together shows people’s positive reception of robots, those simulated human machines. Part 2 is in a similar vein, depicting a society that embraces simulated lives through avatars, and simulated relationships through virtual connections. We may be more connected ever, but we are isolated. Alone, but we are alone together.

In her concluding chapter, Turkle writes:

We brag about how many we have ‘friended’ on Facebook, yet Americans say they have fewer friends than before. When asked in whom they can confide and to whom they turn in an emergency, more and more say that their only resource is their family.

The ties we form through the Internet are not, in the end, the ties that bind. But they are the ties that preoccupy.

And I must mention this case. Turkle has a former colleague, Richard, who has been left severely disabled by an automobile accident. Confined to a wheelchair in his home. He has had his share of abusive carers…

Some… hurt you because they are unskilled, and some hurt you because they mean to. I had both. One of them, she pulled me by the hair. One dragged me by my tubes. A robot would never do that,” he says. And then he adds: “But you know, in the end, that person who dragged me by my tubes had a story. I could find out about it. She had a story.”

For Richard, being with a person, even an unpleasant, sadistic person, makes him feel that he is still alive… For him, dignity requires a feeling of authenticity, a sense of being connected to the human narrative. It helps sustain him. Although he would not want his life endangered, he prefers the sadist to the robot.

Richard might have pointed to what it means to be human. I wish I could quote more, but my post is too long.

Alone Together: Why We Expect More from Technology and Less from Each Other by Sherry Turkle. Basic Books, New York, 2011, 360 pages.

~~~ 1/2 Ripples

CLICK HERE to hear Sherry Turkle talk on reclaiming conversations.

CLICK HERE to an interview with Sherry Turkle

CLICK HERE to read my post “Alone Together by Sherry Turkle, Part 1“

CLICK HERE to read my post “No Texting for Lent and The End of Solitude”

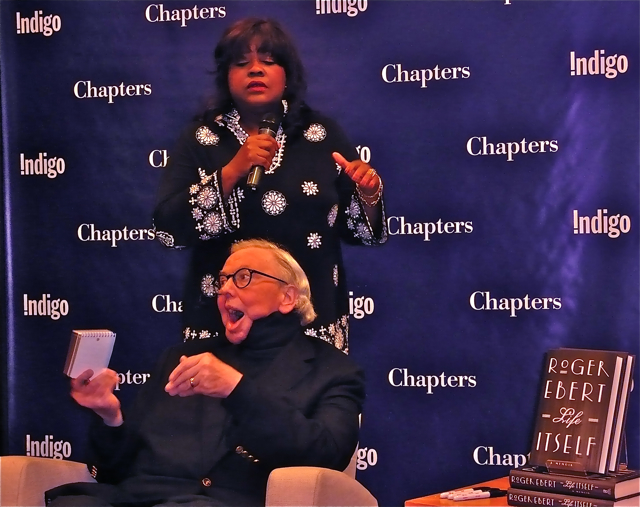

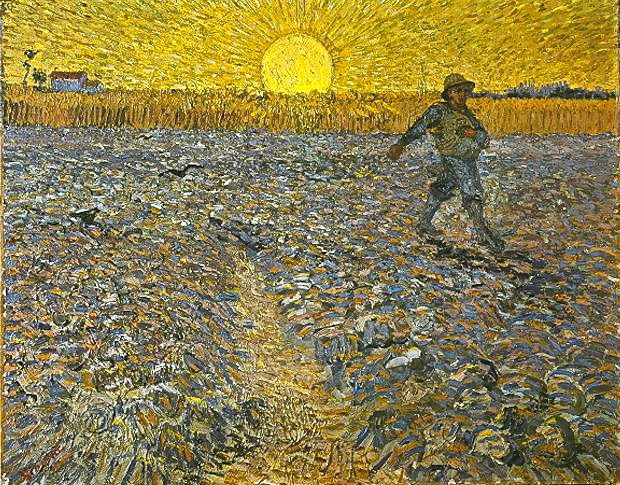

Both photos on this post are taken by Arti of Ripple Effects. Top: One of the Thousand Islands, Kingston, Ontario, Sept. 2007. Bottom: Authenticity & the Networked Self, March, 2011. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.