250th Birth Anniversary of Jane Austen (December 16)

It’s a great loss that Jane died so young, at 41, from a painful illness. The legacy of her six completed novels continue to thrive today. Movie adaptations are still being made, most notable is the upcoming new version of Pride and Prejudice with Emma Corrin as Lizzy, Jack Lowden as Mr. Darcy, and Olivia Colman as Mrs. Bennet. But we will never forget that iconic wet shirt scene of Colin Firth diving into the pond way back in 1995, thirty years ago.

30th Anniversary* of Jane Austen Screen Adaptations:

Pride and Prejudice Austenmania was ignited with this six-part BBC TV series. Andrew Davis’ screenplay brings Colin Firth and Jennifer Ehle together as the pivotal pair. To many, myself included, the definitive version of all the adaptations; yes, my prejudice here.

Sense and Sensibility That same year, 1995, we saw the breakout work of Taiwanese American director Ang Lee, proving his versatility, with Emma Thompson basking in the limelight receiving her Best Adapted Screenplay Oscar.

Persuasion While not as popular as Pride and Prejudice, a novel that shows a more mature writer showing her own sense of wisdom in handling love and life. Ciaran Hinds is an impressive Captain Wentworth.

Clueless One of the first modern renditions of Austen novels. Here’s an American teenager playing Emma in her high school. What follows are numerous contemporary parallels of Austen’s works, like Bridget Jones’s Diary, and across cultures, Bride and Prejudice, From Prada to Nada.

*Jane Austen’s House in Chawton is celebrating the 30th Anniversary of these adaptations with their own special AUSTENMANIA! events.

***

100th Anniversary of the publication of some modern classics, books and poems* Listing a few here:

The Great Gatsby by F. Scott Fitzgerald

One of my all-time favourite books. Filmmaker Baz Luhrmann highlights all the zeitgeist of the jazz age, the wild parties, and the gaudy excess but fails to bring out the deep character of the man behind those façade, a romantic hanging on hope and seeing every obstacle as a green light. My Ripple Review here.

Mrs. Dalloway by Virginia Woolf

This is one example that the movie adaptation is as good as or even surpasses the book, for it shows more than words can tell. While I admire Woolf’s stream of consciousness, both in expression and withholding, director Steven Daldry’s multi-faceted depiction of Clarissa’s internal world projected into the psyche of two other women is exceptional. David Hare’s screenplay adapting Michael Cunningham’s The Hours is an exemplary transposition of literature onto the screen. And watching Meryl Streep, Nicole Kidman and Julianne Moore in one film is sure worth one’s ticket, or time.

The Painted Veil by W. Somerset Maugham

Somerset Maugham is one of those writers who take you to places but still remain intact with his characters, the backdrop of foreign lands are merely that, backdrop, while the characters lead the story. I’ve seen the movie adaptation, and in my Ripple review I had written this: “Transforming great lines from a book into equally inspiring visual story-telling is an arduous task, and it’s something that mere beautiful cinematography cannot suffice.”

Carry On, Jeeves by P. G. Wodehouse

The third of Wodehouse’s 20 Jeeves and Wooster books. Jeeves is a marvellous invention, a character that reminds me of Mr. Carson of Downton Abbey. There are lots of LOL moments. He’s like a Swiss army knife, a tool of multiple usages. Wodehouse makes him more than utilitarian though. In the interactions between employer and butler, the joke always falls on the former. And that’s the fun of it.

No More Parades by Ford Madox Ford

No More Parades is the second book in the Parade’s End tetralogy by Ford Madox Ford (1873-1939) Set in the time of WWI, where poetry was written in the trenches. In its core a love story movingly depicted in the BBC five-episode TV series (2012), one of the most understated and neglected productions. A young Benedict Cumberbatch and Rebecca Hall are the mismatched couple, but it’s the pristine Adelaide Clemens that shines as idealistic suffragette Valentine.

The Hollow Men by T. S. Eliot

‘The Hollow Men’ is the title poem of this collection of poetry by Eliot, astute critic of his times. “We are the hollow men/we are the stuffed men/Leaning together/Headpiece filled with straw.” Alas, a look at our world today one would find how after one hundred years, Eliot’s critique of his society still stands.

*The popular ‘Year Reading Club’ on Kaggsy’s and Simon’s book blogs are featuring the 1925 Club reading event this October, where we read books published in 1925 and share our thoughts in our blogs.

***

50th Anniversary of some iconic movies:

Where were you in 1975? Watched any of these movies in the theatre?

Jaws dir. by Stephen Spielberg

One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest dir. by Miles Forman

The Man Who Would be King dir. by John Houston

Monty Python and the Holy Grail dir. by Terry Gilliam and Terry Jones

Dog Day Afternoon dir. by Sidney Lumet

Barry Lyndon dir. by Stanley Kubrick

The Return of the Pink Panther dir. by Blake Edwards

Three Days of the Condor by Sydney Pollack

Farewell, My Lovely dir. by Dick Richards

Funny Lady dir. by Herbert Ross

***

Not born yet? How about 1985?

40th Anniversary of:

The Breakfast Club dir. by John Hughes

Back to the Future dir. by Robert Zemeckis

The Color Purple dir. by Stephen Spielberg

A Room with a View dir. by James Ivory

Out of Africa dir. by Sydney Pollack

The Purple Rose of Cairo dir. by Woody Allen

Vagabond dir. by Agnès Varda

Witness dir. by Peter Weir

***

Numerous posts on Jane Austen, as well as movies and books mentioned in the above lists are posted here at Ripple Effects. Seek them out using the Search feature on the top of the left sidebar.

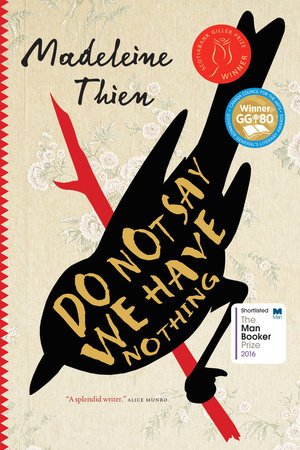

Do Not Say We Have Nothing by Madeleine Thien

Do Not Say We Have Nothing by Madeleine Thien The Noise of Time by Julian Barnes

The Noise of Time by Julian Barnes Cometh the Hour by Jeffrey Archer (#6 of the Clifton Chronicles)

Cometh the Hour by Jeffrey Archer (#6 of the Clifton Chronicles) A totally different tone, but the same historical backdrop. Towles has created an interesting and colourful character, the aristocrat Count Alexander Rostov, kept in house arrest when the Bolsheviks overrun the country. True to his personality and lifestyle – the major consolation of such a misfortune – Count Rostov serves his house arrest in the elegant Moscow Metropol Hotel across from the Kremlin, albeit in a cramped room in the attic. With his always pleasant demeanour, the former aristocrat makes himself at home at the grand hotel, meeting interesting characters, wine and dine to his heart’s content. He stays there for decades, with the historic changes happening outside the four walls of the Metropol: Lenin, Stalin, post-Stalin, and further. As fate would have it, Count Rostov encounters an idealistic youngster named Nina, and years later, takes up guardianship of her daughter Sofia, and thus his life and view begin to turn into something more purposeful. The Metropol makes me think of Wes Anderson’s The Grand Budapest Hotel. Instead of speaking truth to power and get slapped in the face or worse, Count Rostov thinks of an ingenious scheme to beat Power at their game. If I were a filmmaker, this is one to bank on.

A totally different tone, but the same historical backdrop. Towles has created an interesting and colourful character, the aristocrat Count Alexander Rostov, kept in house arrest when the Bolsheviks overrun the country. True to his personality and lifestyle – the major consolation of such a misfortune – Count Rostov serves his house arrest in the elegant Moscow Metropol Hotel across from the Kremlin, albeit in a cramped room in the attic. With his always pleasant demeanour, the former aristocrat makes himself at home at the grand hotel, meeting interesting characters, wine and dine to his heart’s content. He stays there for decades, with the historic changes happening outside the four walls of the Metropol: Lenin, Stalin, post-Stalin, and further. As fate would have it, Count Rostov encounters an idealistic youngster named Nina, and years later, takes up guardianship of her daughter Sofia, and thus his life and view begin to turn into something more purposeful. The Metropol makes me think of Wes Anderson’s The Grand Budapest Hotel. Instead of speaking truth to power and get slapped in the face or worse, Count Rostov thinks of an ingenious scheme to beat Power at their game. If I were a filmmaker, this is one to bank on.