“I’ve had lots of troubles, so I write jolly tales.” ––– Louisa May Alcott

.

My point of contact with Patricia Highsmith’s work is mainly in the movies: Strangers on a Train, The Talented Mr. Ripley, Two Faces of January, and Carol based on her novel The Price of Salt which I’d read. Edith’s Diary, first published in 1977, is a very different work from all the above.

My point of contact with Patricia Highsmith’s work is mainly in the movies: Strangers on a Train, The Talented Mr. Ripley, Two Faces of January, and Carol based on her novel The Price of Salt which I’d read. Edith’s Diary, first published in 1977, is a very different work from all the above.

As the book begins, Edith Howland, 35, her husband Brett, and their ten year-old son Cliffie have just moved into small town Brunswick Corner, Pennsylvania, from New York City. The year is 1955. The reason for the move is for Cliffie to grow up in a country environment with more space to roam. Edith’s diary is a precious possession wherein she records her experiences.

Edith is quick to immerse in the community and makes a few friends. With Gert, she successfully revitalizes the local paper Bugle, and she continues with her freelance writing. It’s Cliffie that’s her main concern. Cliffie isn’t a normal boy. He keeps to himself, is indifferent to his parents, unkind to their cat Mildew, makes no friends and doesn’t do well in school. That’s enough for alarm, but Edith’s attitude is concern mixed with appeasement.

Not long after they’ve moved into their house, Brett’s elderly uncle George comes to live with them, a decision not from mutual consent between the couple. Edith has to take care of George, cook and bring his meals to his bedside, keep the house in good order, write for Bugle and pitch to magazines, all while keeping an amicable social front.

Ten years gone by, life hasn’t aligned much with Edith’s wishes. Far from it. Cliffie can’t make it into any college, no full-time job and turns to alcohol and drugs to pass his days. Old George still hangs in there needing more of Edith’s time and attention. Most devastating to her psyche is Brett, who has left her and moved back to NYC to a new life of his own by marrying his young secretary. Highsmith is meticulous in detailing the psychological world of Edith’s, her frail personality, appeasing her son and yielding to her husband.

But as life’s burdens become heavier and things get gloomier, Edith’s entries in her diary shift to a more and more uplifting tone. She creates a different life for her son in her diary entries, imagining Cliffie successfully graduates from Princeton and begins a good career, marries a sweet girl who later bears her a grandchild.

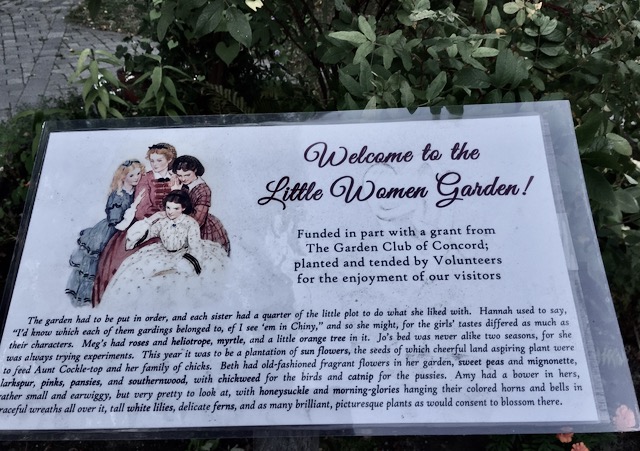

Edith’s diary is an imaginary narrative that’s totally different from her real life. Towards the end, madness takes over and Highsmith’s ending is both shocking and dismissing. No spoiler here. However, reading the book makes me think of a quote from Little Women‘s author Louisa May Alcott:

I’ve had lots of troubles, so I write jolly tales. ––– Louisa May Alcott

What’s the difference between Alcott writing jolly tales and Edith’s detailing an alternative life in her diary? If Edith isn’t writing into a diary, which is supposed to be ‘non-fiction’, isn’t she just creating a work of fiction? Where’s the line between escape and creativity?

Highsmith drops obvious clues for us describing Edith’s sinking deep into the slough of madness as she actually prepares for her imaginary Cliffie’s visit to her home for dinner with wife and son in tow. So, it looks like Highsmith is showing us the demarkation, when the two lives, the imaginary and the real, merge into one, therein lies madness.

But, is Edith’s diary an evidence of madness, or an imaginary work of fiction? Hmm… that would be my question to Highsmith if I were a journalist interviewing her. Now, just let me dwell on that thought some more…

***

Edith’s Diary by Patricia Highsmith, Grove Press, New York, 2018. 393 pages.

Note: Patricia Highsmith’s own diaries will be published in the coming year. Now that would be an interesting read.

Death on the Nile by Agatha Christie

Death on the Nile by Agatha Christie Rebecca by Daphne du Maurier

Rebecca by Daphne du Maurier The Call of the Wild by Jack London

The Call of the Wild by Jack London Voyages of Doctor Dolittle by Hugh Lofting

Voyages of Doctor Dolittle by Hugh Lofting The Invisible Man by H. G. Wells

The Invisible Man by H. G. Wells Brave New World by Aldous Huxley

Brave New World by Aldous Huxley Dune by Frank Herbert

Dune by Frank Herbert Artemis Fowl by Eoin Colfer

Artemis Fowl by Eoin Colfer The Secret Garden by Frances Hodgson Burnett

The Secret Garden by Frances Hodgson Burnett I Know this much is True by Wally Lamb

I Know this much is True by Wally Lamb Little Fires Everywhere by Celeste Ng

Little Fires Everywhere by Celeste Ng Nine Perfect Strangers by Liane Moriarty

Nine Perfect Strangers by Liane Moriarty The Woman in the Window by A. J. Finn

The Woman in the Window by A. J. Finn