Sherry Turkle is the Abby Rockefeller Mauzé Professor of the Social Studies of Science and Technology at MIT, the founder and director of the MIT Initiative on Technology and Self, and a licensed clinical psychologist.

For thirty years, Turkle has been studying the social-psychological aspect of how technology has been changing us humans. The word ‘humans’ has to be emphasized because the first half of her book details her research on The Robotic Movement. Her findings show that we are more and more dependent on technological advancements, in particular, robotics, to solve some of our human problems such as loneliness, friendship, caring for each other, and ultimately, to love and be loved.

Part one of Turkle’s book chronicles how over the decades, the robotic technology has given us simulated pets from Tamagotchi to Furby, simulated real-life humans like My Real Baby, to sociable robots developed as companion and later carers of the elderly, to the latest stage of robots capable to commune with human, and where human and machine almost existing and interacting on an equal level.

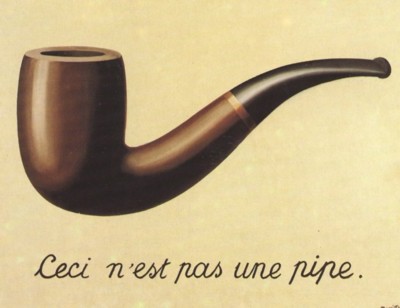

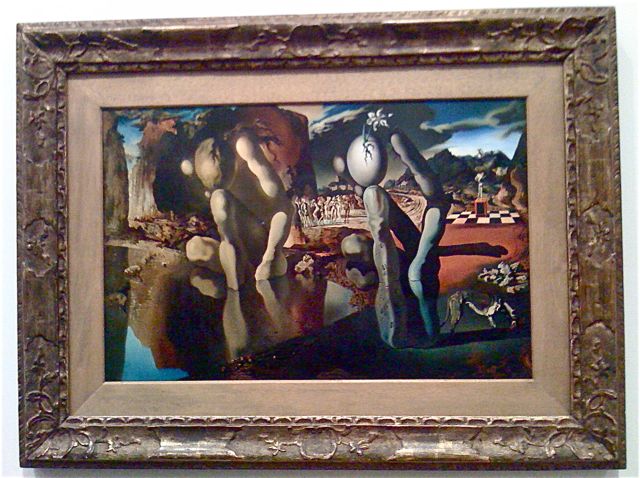

I find myself grasping for the fine line of distinction: what is human? If a machine is programmed to emote and think, is it still a machine? If a machine is created to have a human face, is it more human and less machine? For those who think machines in the form of robots will never replace humans need to read some of Turkle’s research findings. Hopefully we have not passed the point of no return.

From her book, I’m surprised to find how readily people are willing to accept a robot as a friend, a confidant, a companion, a carer, and even an equal. The researchers observe people’s behavior and interactions with the various kinds of robots in real life situations and through interviews. Here are some of the responses, from children to adults:

I want a robot to be my friend… I want to tell my secrets.” (Fred, 8 )

“I could never get tired of Cog (robot)… It’s not like a toy because you can’t teach a toy; it’s like something that’s part of you, you know something you love, kind of like another person, like a baby. I want to be its friend, and the best part of being his friend would be to help it learn… In some ways Cog would be better than a person-friend because a robot would never try to hurt your feelings.” (Neela, 11)

“Kismet, I think we’ve got something going on here. You and me… you’re amazing.” (Rich, 26, talking to the sociable robot Kismet, after showing Kismet the watch his girlfriend gave him and seemingly received some response back from Kismet.)

“I like that you have brought the robot (Paro, a ‘carer’). She (speaker’s mother in a nursing home) puts it in her lap. She talks to it. It is much cleaner, less depressing. It makes it easier to walk out that door. (Tim, 53)

Turkle notes that the reason people are so receptive to robots is because they offer painless solutions to their human need for attention and connection, to be noticed and sought after. They can all be programmed to do these. And for the elderly, a robotic carer can be clean, accurate, and avoid mistreatment and abuse.

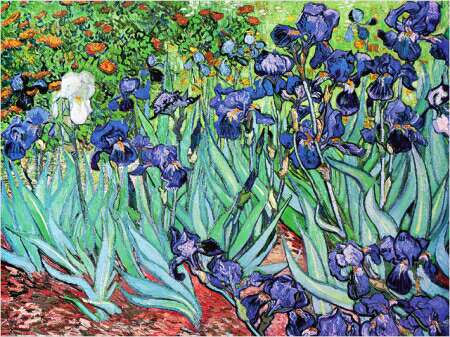

Robotic carers have been placed in nursing homes with very positive results. And the simulated robot My Real Babies are most desirable among many elderlies. In one case Turkle has left a My Real Baby with Edna, 82, who lives in her own home. I almost shudder to read the following observation by Turkle’s research team, when Edna’s granddaughter Gail brings along her 2 year-old daughter Amy to visit:

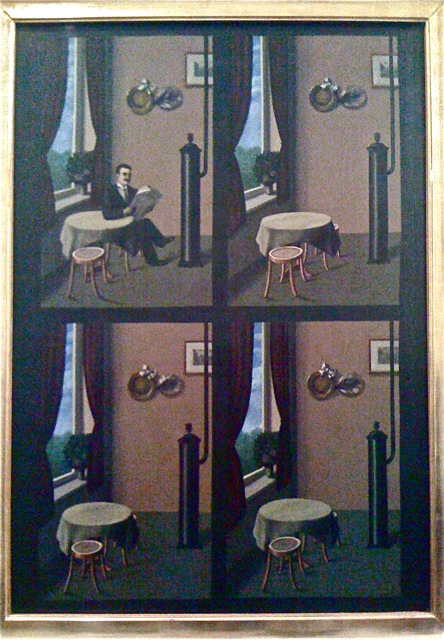

Edna takes My Real Baby in her arms. When it starts to cry, Edna finds its bottle, smiles, and says she will feed it. Amy tries to get her great grandmother’s attention but is ignored…

Edna’s attention remains on My Real Baby. The atmosphere is quiet, even surreal: a great grandmother entranced by a robot baby, a neglected two-year-old, a shocked mother, and researchers nervously coughing in discomfort. (p. 117)

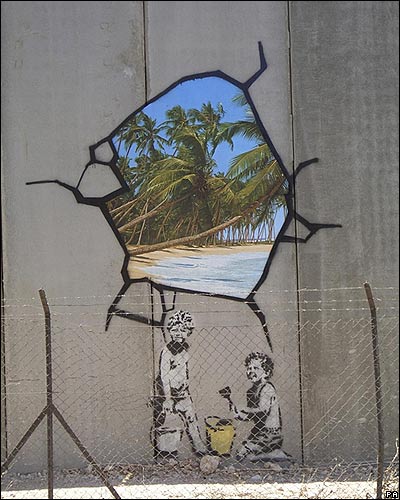

That we can with technology doesn’t automatically lead to that we should. But the issue is complex though. Does it matter that we are engaged with the inanimate and allow it to help us? Should there be a line drawn as to what kinds of tasks we leave to machines, and what we should keep as humans? What is ‘humanness’ after all?

A class of grade five children once posed the question: “Don’t we have people for these jobs?” It is wise enough for these young minds. But, it gets complicated if the issue is: “What if a robot can do a better job?” Then what does that leave us?

It has been a long while since I last posted. For one thing I have been preoccupied with the caring for two elderly parents. Meanwhile, reading through Sherry Turkle’s book requires much more time for thinking and mulling over, definitely not for speed reading. Now that I’ve finished, I need to crystallize my thoughts to write sensibly before I post, as the book deserves. The slow blogger in action… and thanks for waiting. So here is the first part. The second part is even more relevant and timely for us, our networked self. CLICK HERE to go there.

***