While reading van Gogh’s letters is a fascinating journey into the mind of the artist, it is also poignantly heartbreaking. This is an abridged version of van Gogh’s letters, almost all written to his brother Theo from the various places he had stayed from 1872-1890, Holland, Belgium, England and France.

A few decades separate his life from Hemingway’s, but I think he too had his “moveable feast”. To the painter, it’s not Paris, but the open country of southern France, in particular, Arles and St. Remy’s, Provence.

(A corner store in Arles, named after the famous ‘Yellow House’ Van Gogh once lived in)

Unlike Hemingway, van Gogh felt Paris only ‘distracts’. He wrote to his brother Theo after moving to Arles from Paris in February, 1888:

It seems to me almost impossible to be able to work in Paris, unless you have a refuge in which to recover and regain your peace of mind and self-composure. Without that, you’d be bound to get utterly numbed.

While Hemingway sought to “write one true sentence”, van Gogh yearned to reflect what was true through his paintings:

… giving a true impression of what I see. Not always literally exact, rather never exact, for one sees nature through one’s own temperament.

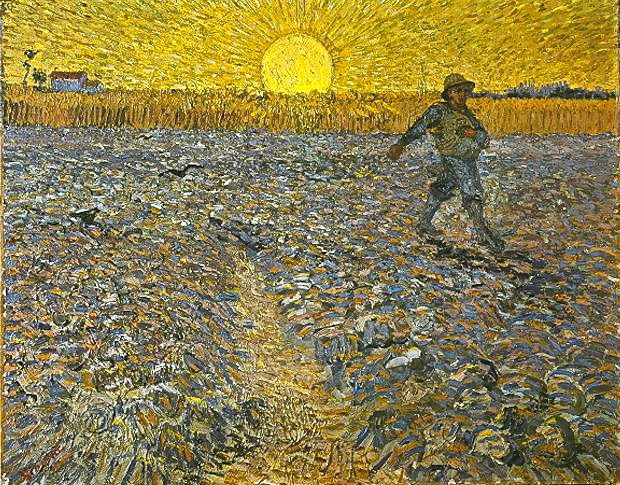

And colours were his tools. Van Gogh began to use a new palette that he did not see in his native Holland. Under the bright Provence sun, the artist excitedly indulged in a myriads of brilliant colours he had not experienced before…”There is that sulphur yellow everywhere the sun lights on.” He eagerly ushered in a new style.

Instead of trying to reproduce exactly what I have before my eyes, I use colour more arbitrarily so as to express myself forcibly… — To Theo from Arles, August 1888

(The Sower)

I believe in the absolute necessity for a new art of colour, of design, and — of the artistic life.”

“But the painter of the future will be such a colourist as has never yet been [emphasis his].

Through the artist’s colourful lens, the view that van Gogh saw was one that I could never imagine. Here he described to his brother Theo a painting he’d finished, in a letter dated September, 1888:

… the starry sky painted actually at night under a gas jet. The sky is greenish blue, the water royal blue, the ground mauve. The town is blue and violet, the gas is yellow and the reflections are russet gold down to greenish bronze. On the blue-green field of the sky the Great Bear sparkles green and rose, its discreet pallor contrasts with the brutal gold of the gas.

(Starry Night)

Many of the letters are descriptions like this to Theo in Paris. Reading them, I can sense the artist’s excitement and joy in capturing everything he saw in Arles:

At the moment I am working on some plum trees, yellowish white, with thousands of black branches. I am using a tremendous lot of colours and canvases…

… it will be to our advantage to make the most we can of the orchards in bloom. I am well started now, and I think I must have ten more, the same subject. You know, I am changeable in my work, and this craze for painting orchards will not last for ever. After this may be the arenas…

His letters alas are also pleas for funds, as he was “literally starving”. With the last fr.5 he had, he’d spend it on canvases. He lived in dire poverty most of his career, damaging his physical and mental health.

I can’t do without colours, and colours are expensive… I cannot get more on credit. And yet I love painting so…

Worse still, his letters are also accounts of anguish, depression, and “unbearable hallucinations.” He desperately sought cures, admitting himself into the asylum in St. Remy’s. Ironically, it was there that he experienced the most prolific period of his life.

(St. Paul’s Hospital at St. Remy’s)

Throughout van Gogh’s numerous letters, there are many beautiful lines, insight into love, art, books, and life. Here are a few:

- “Since I really love there is more reality in my drawings.” — Autumn 1881

- “I would not give a farthing for life, if there were not something infinite, something deep, something real.” — December 1881

- “It is the painter’s duty to be entirely absorbed by nature and to use all his intelligence to express sentiment in his work so that it becomes intelligible to other people. To work for the market is in my opinion not exactly the right way…” — July 1882

- “I assure you that some days at the hospital were very interesting, and perhaps it is from the sick that one learns how to live.” — January 1889

- “I took advantage of my outing to buy a book… I have devoured two chapters of it… This is the first time for several months that I have had a book in my hand. That means a lot to me and does a good deal towards my cure.” — March 1889

- “What I should very much like to have to read here now and then, would be a Shakespeare… What touches me, as in some novelists of our day, is that the voices of these people, which in Shakespeare’s case reach us from a distance of several centuries, do not seem unfamiliar to us. — From St. Remy’s Hospital, June 1889.

But tragically, van Gogh succumbed to his mental illness. In July, 1890 two months after moving back to Auvers, north of Paris, he went out to the open fields and shot himself. Two days later he died from his gunshot wound. He was 37.

The Letters of Vincent van Gogh to his Brother and Others. Introduction by his sister-in-law Johanna van Gogh-Bonger, abridged by Elfreda Powell, Published by Constable & Robinson Ltd., 2003, 324 pages.

***

The is my last post for the blogging event Paris in July hosted by Karen of BookBath, and Tamara of Thyme for Tea. My other post is “A Moveable Feast (Restored Edition) by Ernest Hemingway.”

To read my travel post from last August “Arles: In The Steps of Van Gogh” CLICK HERE.

Photos: Van Gogh’s paintings, from Wikimedia Commons, Public Domain. Arles and St. Remy’s by Arti of Ripple Effects, August, 2010.

To read all the 900 letters of van Gogh online, go to this excellent site of the Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam.