The idea of a baby born as an old man and then grows younger––a reverse trajectory of the human experience––is the premise in F. Scott Fitzgerald’s short story published in 1922, reviewed in my previous post. Prompted by a remark made by Mark Twain, Fitzgerald unleashed his imagination and wrote the story.

The tale was adapted into a 2008 movie directed by David Fincher who brought it all the way to the Oscars with 13 nominations the next year. I watch it for the first time in 2020 and am surprised to find its relevance: the fear of strangeness in our age of xenophobia.

As for the 13 Oscar nominations, the movie won only three: Art Direction, Makeup, and Visual Effects. These are difficult feats and deserving wins. Unlike the Academy’s (and some critics’) aloofness in embracing the film’s other achievements, I much appreciate the adapted screenplay and Fincher’s 166 minute visual rendition.

Here’s an exemplar of how a film adaptation diverges from the original literary source and yet still keeps its main concept, but instead of faithfully following the thin, short story, carries it to a different direction, creating an expanded and more gratifying version.

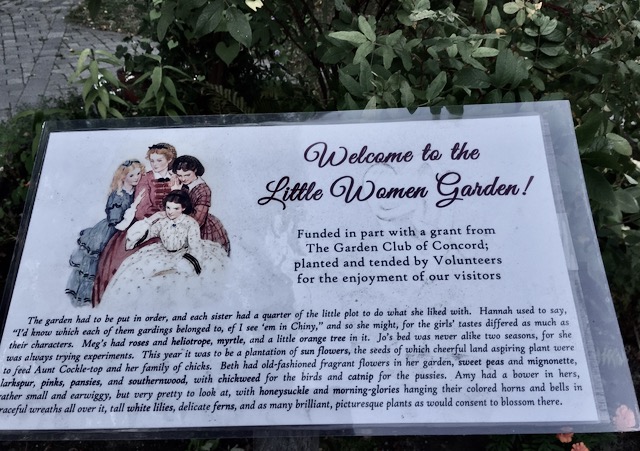

Screenwriters for the adaptation are Eric Roth and Robin Swicord. Roth is known for his Oscar winning adapted screenplay for Forrest Gump (1994), and Robin Swicord for her 1994 version of Little Women. They had chosen to turn Fitzgerald’s farcical, acerbic fantasy into a serious film in the vein of magical realism. The magic lies in the imaginary, reverse growth trajectory; the realism is love.

This is not just about love between two star-crossed lovers, Benjamin (Brad Pitt) and Daisy (Cate Blanchett), but about a woman with a huge heart, Queenie (Taraji P. Henson), who embraces a Gollum-like baby abandoned at her doorstep. Instead of a non-mentioned mother in Fitzgerald’s story, Queenie raises Benjamin with devoted affection. There’s love and acceptance as well from those in the old folks lodging house where Queenie works. Further, the movie adds one more layer, and that’s Daisy at her deathbed, sharing the story of her lost love with her daughter Caroline (affectively played by Julia Ormond), leaving her with a legacy of love.

The film makes amends to the sardonic tone of the short story by creating a moving love story. For a short period in their lives, both Benjamin and Daisy are of approximate age, but such joy doesn’t last as one grows older and the other younger. Yet unlike the short story, their love endures, for as long as one can hold on to it despite separation. And we find out that one can, all the way to her deathbed; the other is just too young to remember. What’s left is the transience of time and inevitable fate.

The setting is early 20th century on the cusp of WWI in New Orleans where Benjamin is born, and not 1860 Baltimore. As he grows younger, Benjamin goes through WWII instead of the Spanish-American War in the short story. The movie starts off with a modern time with Daisy’s final hours revealing to her daughter who her real father is. That’s 2005 New Orleans, during a hurricane when the hospital is preparing to evacuate. A disastrous storm as a backdrop in the telling of a billowy story. A name to denote the significance: Katrina.

The movie is a divergence for Fincher too considering he’s a master of crime thrillers –– Zodiac came out just a year before in 2007, and more recently Gone Girl in 2014, Benjamin Button is Fincher’s only ‘romantic’ drama (The Social Network, 2010, is drama but definitely not ‘romantic’). Crafted in signature Fincher styling with low-light, sepia colour to enhance the period effects, the aesthetics in set design and cinematography bring out the notion of ‘every frame a painting’.

Brad Pitt’s understated performance characterizes Benjamin aptly. Instead of remaining ‘the other’, Benjamin strives to connect, albeit in a gentle and quiet way. His love at first sight with then 7 years-old Daisy is a poignant encounter. Elle Fanning is a perfect cast. A child who holds no prejudice, she’s fascinated by the ‘strangeness’ in Benjamin. The Heart is a Lonely Hunter comes to mind.

Other curious finds: music by Alexandre Desplat, Tilda Swinton in some memorable sequences, Queenie’s husband Tizzy played by now two-time Oscar winner Mahershala Ali (Green Book, 2018 and Moonlight, 2016).

You probably have watched it before when the film first came out. How the world has changed in just twelve years. Watching it again now would probably bring you a different feel, and more relevance.

~ ~ ~ Ripples

***

A Girl Missing directed by Koji Fukada (Japan) North American Premiere. Fukada’s previous film, Cannes’ Un Certain Regard Jury Prize winner Harmonium (2016) grabbed me as a concoction of Hitchcockian suspense and poignant family drama. Excited to see his newest work at TIFF.

A Girl Missing directed by Koji Fukada (Japan) North American Premiere. Fukada’s previous film, Cannes’ Un Certain Regard Jury Prize winner Harmonium (2016) grabbed me as a concoction of Hitchcockian suspense and poignant family drama. Excited to see his newest work at TIFF. A Hidden Life directed by Terrence Malick (USA, Germany) Canadian Premiere. Based on the true story of Austrian farmer and conscientious objector Franz Jägerstätter, who refused to join the German army in WWII. I expect this newest Malick film to be another soul-stirring work.

A Hidden Life directed by Terrence Malick (USA, Germany) Canadian Premiere. Based on the true story of Austrian farmer and conscientious objector Franz Jägerstätter, who refused to join the German army in WWII. I expect this newest Malick film to be another soul-stirring work. The Audition directed by Ina Weisse (Germany, France) World Premiere. Women play major roles in this production as director, screenwriter and cinematographer. But the main attraction for me is actor Nina Hoss, whose riveting performance won her high acclaims in the German films Phoenix (2014) and Barbara (2012).

The Audition directed by Ina Weisse (Germany, France) World Premiere. Women play major roles in this production as director, screenwriter and cinematographer. But the main attraction for me is actor Nina Hoss, whose riveting performance won her high acclaims in the German films Phoenix (2014) and Barbara (2012). Coming Home Again dir. by Wayne Wang (USA/Korea) World Premiere. Wang brought Amy Tan’s The Joy Luck Club to mainstream cinema in 1993, telling generational

Coming Home Again dir. by Wayne Wang (USA/Korea) World Premiere. Wang brought Amy Tan’s The Joy Luck Club to mainstream cinema in 1993, telling generational The Personal History of David Copperfield dir. by Armando Iannucci (UK) World Premiere. As a book-to-movie enthusiast, I won’t miss this one. What more, the cast looks impressive, and postmodern. Dev Patel of Slumdog Millionaire (2008) fame will play Davy, Tilda Swinton as Betsey, Hugh Laurie as Mr. Dick, and Ben Whishaw the villain Uriah Heep. Turning a 800+ page classic into a two-hour movie is as daunting as Davy’s life journey. But I reserve my judgement.

The Personal History of David Copperfield dir. by Armando Iannucci (UK) World Premiere. As a book-to-movie enthusiast, I won’t miss this one. What more, the cast looks impressive, and postmodern. Dev Patel of Slumdog Millionaire (2008) fame will play Davy, Tilda Swinton as Betsey, Hugh Laurie as Mr. Dick, and Ben Whishaw the villain Uriah Heep. Turning a 800+ page classic into a two-hour movie is as daunting as Davy’s life journey. But I reserve my judgement. The Goldfinch dir. by John Crowley (USA) World Premiere. The adaptation of Donna Tartt’s Pulitzer Prize-winning novel is helmed by the same director as Brooklyn (2015), with adapted screenplay by Wolf Hall and Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy scribe Peter Straughan. Looks like a top-notch collaboration.

The Goldfinch dir. by John Crowley (USA) World Premiere. The adaptation of Donna Tartt’s Pulitzer Prize-winning novel is helmed by the same director as Brooklyn (2015), with adapted screenplay by Wolf Hall and Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy scribe Peter Straughan. Looks like a top-notch collaboration. Hope Gap directed by William Nicholson (UK) World Premiere. This is Nicholson’s second directorial feature which he also wrote. His other screenplays include Les Misérables (2012) and Gladiator (2000) among many others. But what draw my attention are the duo who play a couple at the brink of a marriage breakdown, Bill Nighy

Hope Gap directed by William Nicholson (UK) World Premiere. This is Nicholson’s second directorial feature which he also wrote. His other screenplays include Les Misérables (2012) and Gladiator (2000) among many others. But what draw my attention are the duo who play a couple at the brink of a marriage breakdown, Bill Nighy Parasite directed by Bong Joon-ho (S. Korea) Canadian Premiere. This year’s Palme d’Or winner at Cannes. From the description, it echoes Kore-eda’s Shoplifters, last year’s Cannes winner. But Bong’s audacious and creative styling could make this a fresh approach to the subject of social inequality. Lee Chang-dong’s Burning (2018) also comes to mind.

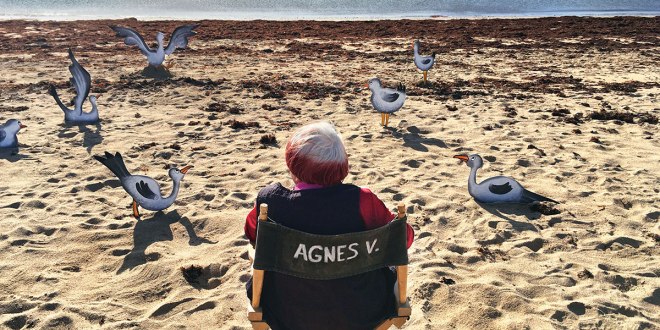

Parasite directed by Bong Joon-ho (S. Korea) Canadian Premiere. This year’s Palme d’Or winner at Cannes. From the description, it echoes Kore-eda’s Shoplifters, last year’s Cannes winner. But Bong’s audacious and creative styling could make this a fresh approach to the subject of social inequality. Lee Chang-dong’s Burning (2018) also comes to mind. Varda by Agnès directed by Agnès Varda (France) Canadian Premiere. After watching the late French New Wave auteur Agnès Varda’s documentary Faces Places (2017), I’d been looking for this, her last work. Excited to know there will be a special event at TIFF 19 with the screening of Varda by Agnès plus a bonus post-film discussion by a panel of filmmakers.

Varda by Agnès directed by Agnès Varda (France) Canadian Premiere. After watching the late French New Wave auteur Agnès Varda’s documentary Faces Places (2017), I’d been looking for this, her last work. Excited to know there will be a special event at TIFF 19 with the screening of Varda by Agnès plus a bonus post-film discussion by a panel of filmmakers.