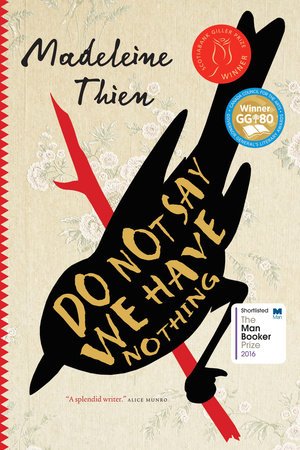

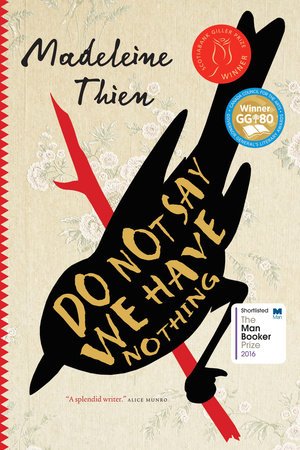

April 3rd UPDATE: Do Not Say We Have Nothing shortlisted for the Baileys Prize.

***

First the Booker, then the Giller and the GG, and now longlisted for Baileys Women’s Prize for Fiction, this voice must be heard. I thank Asian American Press for allowing me to post my review here in full, and Penguin Random House Canada for my reviewer’s copy.

***

Just a few months after it was published in May, 2016, Madeleine Thien’s Do Not Say We Have Nothing was shortlisted for a Booker Prize and had won the top two Canadian literary awards, the prestigious Scotiabank Giller Prize and the Governor General’s Award for fiction. That is extraordinary achievements for the Vancouver born, Montreal based writer.

Thien creates her third novel on a large canvas, spanning from the decades leading to Mao’s Cultural Revolution in 1960’s China and onward to the Tiananmen Square protests and government crackdown in 1989. Even though her novel does not stem directly from a personal experience like others’ such as Dai Sijie’s semi-autobiographical Balzac and the Little Chinese Seamstress, or the eye-witness account of journalist Jan Wong’s Red China Blues, Thien’s outsider’s stance is far compensated by her extensive and detailed research, not just 20th Century history of China but down to the streets and local teahouses. Further, the absence of a first-person experience is replaced by an exuberance of imaginary characters and storytelling, all intricately woven with actual accounts of historical figures and events.

While not being an eye-witness, Thien’s cultural lineage could have brought her into a kind of insider’s realm. Born to Malaysian-Chinese immigrant parents in Canada, Thien’s previous writing had depicted the unique perspective framed by her upbringing. The stories in her collection Simple Recipes (2001) have revealed poignantly the cultural and generational conflicts that could exist in a North American Asian family. Further, Thien’s previous novel Dogs at the Perimeter (2011) had prepared her well to venture into the abyss of human atrocity, with the backdrop of Khmer Rouge’s infamous killing fields in Cambodia. Do Not Say We Have Nothing presents a larger landscape and a more ambitious undertaking than her previous works.

This is how the book opens, simple yet powerful:

“In a single year, my father left us twice. The first time, to end his marriage, and the second, when he took his own life.”

Here we hear a voice, seemingly nonchalant, but still lucid and sad. This is the voice of the protagonist, Marie. She was ten years-old and living with her mother in Vancouver when she learned of her father’s suicide in Hong Kong. The year was 1989. Not long after this news, Marie’s mother took in nineteen-year-old Ai-ming from China, alien and undocumented, escaped out of the country during the Tiananmen crackdown.

Ai-ming’s short refuge in Marie’s home bonded the two like sisters. As well, she opened the eyes of young Marie to life inside a totalitarian regime. The radio played only eighteen pieces of approved music. Her father, Sparrow, would listen to illegal music secretly and hum the melody of his own composition when he thought no one was around. Ai-ming’s interactions with Marie have prodded her—now twenty years later and a professor of mathematics at Simon Fraser University—to search for the truth about her father Kai and his mentor, Ai-ming’s father Sparrow, as well the tragic personal and national history that had consumed their lives.

With Ai-ming’s help, Marie and her mother began to decipher a secret hand-copied manuscript Kai had kept, “The Book of Records”, passed on to him from Sparrow, an allegorical account of their life in China, outward journey and clandestine dreams, “things we never say aloud”. As a young child, Marie was overwhelmed. Now as an adult, she is driven all the more to pursue the truth of her own family history.

It is not easy to follow Thien’s story in the first few chapters as there are many characters introduced with their own backstory. Time frame switches back and forth, spanning two continents. As I entered Chapter 4, I had to draw up a character chart, as I was looking into a kaleidoscope of three generations and other colourful figures against tumultuous events. If the book had included such a chart at the beginning, it would be most helpful for readers.

We follow Marie’s discovery as she comes to learn that her father Kai used to be a gifted piano student at the Shanghai Conservatory of Music, and Sparrow, a prominent composer, was his teacher there. Together with Sparrow’s young cousin Zhuli, a prodigious violin student, the three forged an unspeakable bond. They cherished each other’s dreams with youthful fervors, which all were altered if not extinguished when Mao ignited his Cultural Revolution.

When she was small, Zhuli discovered by accident her parents’ secret storage where they hid their treasures of western classical music records and books. This led to her parents, Swirl and Wren the Dreamer, to be charged as counter-revolutionary. They were publically criticised and humiliated, then sent to separate labour camps in the remote northwest of China in the name of ‘re-education’. Zhuli was taken secretly to her aunt, Big Mother’s Knife, Sparrow’s mother, and there she grew up. The woman who brought her there had met her aunt only once while on the train. As she ate a lot of the White Rabbit brand candies, we know her by that name. The White Rabbit told Zhuli about her parents’ situation matter-of-factly:

“They’ve been sent for re-education, that’s all… Since you’ve never been educated at all, it seemed pointless to send you along with them.”

This is just one incident where Thien deftly dispenses humour amidst somber events. This is what makes the book enjoyable to read. The subtle humour often is the wrapping of the resilience of human spirit hidden among tragic happenings.

Thien’s story is embedded in historical facts. The prestigious Shanghai Conservatory of Music was shut down in 1966 during the Cultural Revolution, its five hundred pianos destroyed, denouncement and physical battering of the professors and students had resulted in deaths and suicides. Bearing the brunt of the persecution was the unyielding Conservatory President He Luting, beaten but not bent.

Due to their political affiliation, Sparrow’s parents Big Mother Knife and Ba Lute are spared, but what remains in Sparrow is a compromising existence, being sent to work as a factory work for twenty years after the shutdown of the Conservatory. Kai the pragmatist chooses to follow the mainstream and becomes a Red Guard. Young Zhuli sets foot on a tragic path.

With such a setting, it is only natural that Thien would use classical music as the leitmotif of her composition. Shostakovich, Beethoven and Bach are like witnesses to the unfolding of human atrocity, their melodies the fuel that sustains whatever internal fervour that remains. Shostakovich, himself a composer treading a precarious line between authenticity and self-preservation under Stalin’s rule, is an apt metaphor of the situation the trio have to face. The different choices made by Sparrow, Kai and Zhuli well represent the paths that are opened to an artist facing political persecutions.

On another note, and true to her Canadian root, Thein lets pianist Glenn Gould and his two recordings of Bach’s Goldberg Variations be a recurring motif in her story. Bach’s ethereal and invigorating theme and variations belong to Sparrow, the sustenance for his inner life despite deadening circumstances outside.

As the canvas is huge, Thien’s subject matters are numerous. The details and complexity may be a hindrance to readers’ enjoyment. Yet Thien’s voice is close and personal. Do Not Say We Have Nothing, the title taken from the workers anthem the ‘Internationale’, deserves our listening ears. As an instructor of the then newly established MFA Program in Creative Writing at City University of Hong Kong from 2010, Thien experienced first-hand the abrupt cancellation of the program in 2015 “as a result of internal and external politics” as stated in her Acknowledgement at the back of the book. In her article in The Guardian (May 18, 2015), she notes that students from the Program had published essays in support of the Occupy Central student-led democracy movement, the ‘Umbrella Revolution’, that brought Hong Kong to a standstill. That personal experience could well have informed and given her the potent, insider’s voice in her novel writing.

***

~ ~ ~ ~ Ripples

Do Not Say We Have Nothing by Madeleine Thien

Do Not Say We Have Nothing by Madeleine Thien The Noise of Time by Julian Barnes

The Noise of Time by Julian Barnes Cometh the Hour by Jeffrey Archer (#6 of the Clifton Chronicles)

Cometh the Hour by Jeffrey Archer (#6 of the Clifton Chronicles) A totally different tone, but the same historical backdrop. Towles has created an interesting and colourful character, the aristocrat Count Alexander Rostov, kept in house arrest when the Bolsheviks overrun the country. True to his personality and lifestyle – the major consolation of such a misfortune – Count Rostov serves his house arrest in the elegant Moscow Metropol Hotel across from the Kremlin, albeit in a cramped room in the attic. With his always pleasant demeanour, the former aristocrat makes himself at home at the grand hotel, meeting interesting characters, wine and dine to his heart’s content. He stays there for decades, with the historic changes happening outside the four walls of the Metropol: Lenin, Stalin, post-Stalin, and further. As fate would have it, Count Rostov encounters an idealistic youngster named Nina, and years later, takes up guardianship of her daughter Sofia, and thus his life and view begin to turn into something more purposeful. The Metropol makes me think of Wes Anderson’s The Grand Budapest Hotel. Instead of speaking truth to power and get slapped in the face or worse, Count Rostov thinks of an ingenious scheme to beat Power at their game. If I were a filmmaker, this is one to bank on.

A totally different tone, but the same historical backdrop. Towles has created an interesting and colourful character, the aristocrat Count Alexander Rostov, kept in house arrest when the Bolsheviks overrun the country. True to his personality and lifestyle – the major consolation of such a misfortune – Count Rostov serves his house arrest in the elegant Moscow Metropol Hotel across from the Kremlin, albeit in a cramped room in the attic. With his always pleasant demeanour, the former aristocrat makes himself at home at the grand hotel, meeting interesting characters, wine and dine to his heart’s content. He stays there for decades, with the historic changes happening outside the four walls of the Metropol: Lenin, Stalin, post-Stalin, and further. As fate would have it, Count Rostov encounters an idealistic youngster named Nina, and years later, takes up guardianship of her daughter Sofia, and thus his life and view begin to turn into something more purposeful. The Metropol makes me think of Wes Anderson’s The Grand Budapest Hotel. Instead of speaking truth to power and get slapped in the face or worse, Count Rostov thinks of an ingenious scheme to beat Power at their game. If I were a filmmaker, this is one to bank on.

A Man Called Ove by Fredrik Backman

A Man Called Ove by Fredrik Backman Beauty and the Beast

Beauty and the Beast

The Handmaid’s Tale by Margaret Atwood

The Handmaid’s Tale by Margaret Atwood Lion by Saroo Brierley (Memoir originally titled A Long Way Home)

Lion by Saroo Brierley (Memoir originally titled A Long Way Home) The Nightingale by Kristin Hannah

The Nightingale by Kristin Hannah The Zookeeper’s Wife by Diane Ackerman

The Zookeeper’s Wife by Diane Ackerman